HDR Photo Gallery Slickrock Trail Moab

.

.

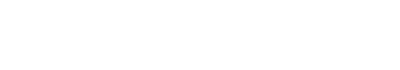

The world famous Slickrock Trail in Moab Utah

.

The Slickrock Trail is THE Trail that put Moab on the map, and is probably the worlds most famous trail. Mountain Bikers from around the globe travel to Moab to ride the Slickrock Trail.

There is no doubt that the Slickrock Trail is as fantastic as it is unique, but it is a trail that I have done numerous times, and I never get very exited about the thought of riding the Slickrock Trail. The crowds on this trail can be unbearable, and on a busy day, there are actual waiting lines in front of certain sections of this trail.

So, does the Slickrock Trail live up to it’s world famous reputation?… read on….

.

.

Nearby Town: Moab

Length: 9.85 miles

Trail Type: Lollipop

Skill Level: [what the books say] Technically very difficult to extremely dangerous. Physically very difficult to abusive

Skill Level: [My Opinion] Technically moderate. Physically demanding

Duration: Book say’s 2-3 hours my time 2.45 hours

Trailhead Elev: 4,575 feet

Top Elev: 4,802 feet

.

This trail is VERY difficult and dangerous. Do not ride alone, but do not bring along you family, your girlfriend, or anyone that you love who is not an advanced rider. Despite the fact that the trail is shown on the Discovery Channel for kids to drool over, it is extremely dangerous and parents should exercise extreme caution with children under 18 (or over) who want to ride here. You could get them into serious trouble. The Slickrock Trail is VERY well marked with painted white lines like the middle of a highway, and there are yellow caution markers and black diamonds to warn you of deadly sections ahead. Be sure to watch for these warnings after you hit the main loop at mile 2.5. Hills on the trail are short, but grueling and very steep. If you let you momentum carry you it could get you into trouble on twisty sections with off-camber turns, but mostly it is momentum that will allow you to ride up the really steep stuff. Traction is fantastic, except when wet or icy. Watch out for winter! Trail Surface: slickrock, obviously, with a painted white line guiding you into the most outrageous situations. At times it is like riding on the outside edge of a 300-foot high basketball.

.

The first time ever did the Slickrock Trail was 4 years ago, I had just arrived in the USA, and did not realize just how popular this trail actually was. I arrived at the parking lot at about 11am on a Saturday, just to find the parking lot completely full, which meant that there were probably 100’s of riders on the Trail… not a good first impression for me, seeing as I’m an unsociable bastard!!

Now whenever I do the Slickrock Trail I leave at the crack of dawn on a weekday. This time around I was at the trailhead at 7am.. at an empty parking area!!.

Having the Slickrock Trail to yourself as the sun comes up is just a fantastic experience, and I was loving every second of it. It’s probably ‘cos I’m getting older, but it seems like the trail gets more strenuous each year, but because it’s such a fantastic trail you tend to forget you are busting your lungs.

For a fantastic 2.45 hours I did not see a single person on the trail, the first people I saw was just 10 min. the trailhead, just starting the ride.

You can love the Slickrock or you can hate the Slickrock, and it will be your timing that decides which one it will be. The first time I hated it, it was like Disneyland . But when planned right ( if possible) the Slickrock Trail is without doubt an absolute Gem of a trail, and it deserves to be one of the worlds most famous mtb trail.

Traffic on Trail : On this early ride I had the trail to myself. However this trail can be a zoo

Wild Life : Definitely don’t need it on this scenic trail

Scenery : Absolutely Fantastic Moab Scenery.

Other : If possible do an early weekday ride. On weekends / holidays the trail can be VERY busy.

This Slickrock Trail review is proudly sponsored by :

Moab Rim Campark

At Moab Rim Campark mountain bikers will definitely feel at home among other mountain bikers at this Mountain Biker Friendly Campgroud.

Bike wash, grassy shaded tent sites with stunning views, Full hook ups, semi hook ups, cabins, group shelters, sheltered areas to tinker on the bikes, and lots more.The Slickrock Trail is just a 6 min. drive from your campsite.

Moab Rim Campsite has been recommended by “Mountain Bike Mayhem” 4 years running.Mountain Bikers get 10% discount, just bring your bike(s) and mention MOUNTAIN BIKE MAYHEM

For more info vist : Moab Rim Campark

.

.

.

We all know what a CamelBak is, and most of us own at least one Camelbak, but not many people know the history behind the CamelBak… Until now that is..

An avid cyclist living in the scorching heat of central Texas, Chuck Hunter staggered into a bike shop in 1997 and says he succumbed to a “cute” saleswoman’s pitch. He left wearing a water-filled backpack with a tube extending to his mouth so that he could drink without reaching for a water bottle.

Two years after that first sip, Mr. Hunter quit his job at Lockheed Martin Corp. to join the company that made the backpack-canteen, CamelBak Products LLC. At the time, the small firm had a devoted clientele of mountain bikers and counterculture types; for example, CamelBaks were ubiquitous at Burning Man, a radical art festival held each summer in the Nevada desert.

Mr. Hunter, a former fighter pilot, sensed an emerging market among a different breed of desert dweller: the U.S. soldier. Now CamelBak’s senior vice president for government, military and industrial business, he has turned the Petaluma, Calif., company into a global leader in so-called hydration systems, selling several million backpacks to troops in the U.S. and some 50 foreign armies. The Pentagon, which recently placed a $17 million order so that it can issue CamelBaks to all soldiers heading to Iraq and Afghanistan, is the company’s biggest customer.

That a cycling accessory could became the canteen of choice for soldiers around the world demonstrates how innovative nondefense companies have fueled growth by capitalizing on the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and the ensuing wars. Even before the London bombings this month, Britain had approved funds to equip police and first-responders with CamelBak systems designed to keep drinking water safe in a chemical or biological attack. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s new emphasis on unconventional threats heralds further growth potential for CamelBak.

Other consumer products, such as Oakley Inc. sunglasses, Garmin Ltd. handheld global-positioning-system units and Under Armour clothing, have found fresh outlets in military sales. But military products have become CamelBak’s dominant business. Instead of the “Hydration on the Move” motto geared to granola-eating fitness buffs, CamelBak’s current slogan is “Hydrate or Die” — emblazoned next to a flame-emitting skull.

CamelBak contends that pivoting between the two markets has helped product development. “The beauty of this company is that military requirements drive innovation and durability, and that goes right down the line to the recreational products,” says Mr. Hunter. For instance, CamelBak developed sturdier materials and a silver-based, antigerm lining to keep water clean for troops, and then adapted these for cheaper retail packs. The company’s products retail for between $25 and $120, and some military packs cost up to $200.

CamelBak was founded in 1989 in Texas by Michael Eidson, who concocted a hands-free drinking system because he felt that reaching for a bottle during bike races risked collisions. The prototype consisted of medical tubing and a plastic intravenous drip bag stuffed into a sock and attached to the back of a shirt. His timing was auspicious: The advent of mountain biking, ultramarathons and other extreme sports created a market-in-waiting.

The 1991 Gulf War also helped. Navy SEALs and special-forces troops who were biking enthusiasts took their own CamelBaks into combat. Word spread, as did CamelBak’s civilian models on the shelves of military exchanges. In 1995, San Francisco firm Kransco, which had marketed Frisbees, Hula Hoops and Boogie Boards as a previous owner of Wham-O Inc., bought CamelBak for $4 million and stepped up military sales by introducing camouflaged models.

But the real military push started in 1999, when Mr. Hunter arrived. CamelBak launched a military line of products and moved to California’s Sonoma County wine district north of San Francisco. Here, it set up a research center to develop products that could meet the Pentagon’s exacting standards.

As much as soldiers liked the CamelBak concept, early models tended to “burst when grunts fell backwards onto them,” says CamelBak R&D head Robert Choi. “It’s harder to carry and deliver water than you’d think,” he adds, walking through a lab where machines stretch, twist, squeeze and rapidly age polyurethane and silicone parts.

CamelBak’s proprietary drinking nozzle, or bite valve, gets compressed 10,000 times to ensure it won’t leak after three years of combat use. The company says it spent $1 million developing a reservoir liner to protect water in a sarin or mustard-gas attack. CamelBak has received 70,000 orders for this “chem-bio” water reservoirs since its launch last September, Mr. Hunter says. Belgium ordered several thousand units and has mandated that new gas masks must be compatible with CamelBak tube adapters.

Feedback from soldiers has been as important as lab tests in molding products. Snipers wanted a sleek, body-hugging pack, so CamelBak designed a 3.2-quart unit — enough for three hours of activity — that can fit under bullet-proof vests.

For a different kind of stealth, CamelBak worked with Dupont Co. and other companies to develop backpack material, straps and buckles that reduce infrared detection. CamelBak markets some two dozen military models, carrying as little as 1.6 quarts of water and no gear to packs that can hold 6.3 quarts of water and seven times that volume in gear.

“Marines love them. Very rarely these days do you see a Marine without a CamelBak cinched to his back,” says Col. Michael Belcher, who commanded a Marine battalion in Iraq and is now based in the U.S. “There’s less sloshing back and forth, and no hip pain.”

Whereas soldiers used to hook three one-quart canteens onto their belts, now they typically carry a 3.2-quart CamelBak and one canteen — which they might use only to refill the CamelBak. CamelBaks are part of the survival kits packed into ejection seats in many Air Force fighter planes.

In 2003, New York investment bank Bear Stearns Cos. bought CamelBak for more than $200 million. Bear Stearns doesn’t disclose CamelBak’s sales and profit figures. With more than 90% of the U.S. military market and solid brand awareness among troops, “We’re like Kleenex. Everyone calls a hydration system a CamelBak,” says product manager Shawn Cullen. The company’s main military competitor is its biggest customer: The Army, working with a former canteen company, has fielded a similar hydration system.

CamelBak has a host of challengers in the civilian market, such as VF Corp.’s JanSport and North Face brands, but is counting on its brand recognition, new recreational models and a thrust into products for industrial workers to keep growing.

After branching out from cycling into running, skiing and hiking packs, CamelBak more recently has launched products for hunting, children and women — a line that features tapered packs, softer materials and higher chest straps. Law-enforcement packs include easy-access pouches for weapons. A horseback-riding line is in the offing. Customers bombard the company with suggestions for packs designed to fight dehydration in every activity from fly fishing to plant watering. “Some uses could hurt the brand a bit,” says Glenn Gross, CamelBak’s chief executive.

Mr. Hunter’s search for industrial customers has him pressing the flesh at events such as the World of Concrete trade show. But his work isn’t done with the military. CamelBak must ensure, he says, that “the canteen is on the way out.”

.